Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...All prices are in All prices are in GBP

Categories

- Home

- Blog History Revisited

- Counterfeiters

Blog History Revisited - Counterfeiters

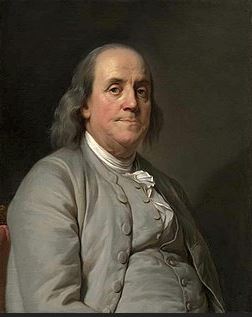

Benjamin Franklin & Mother Nature Thwart Counterfeit Colonial Banknotes

Posted by ©Sandra Ker, Antiquarian Print Gallery 1989-2021, South Australia. Dealer in Antique Prints. www.historyrevisited.com.au on 5th Mar 2021

If "Necessity is the Mother of Invention"...

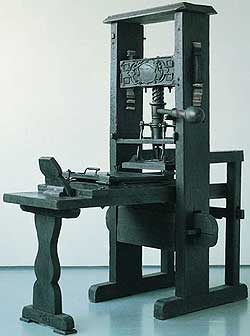

Many of the world’s inventions were often a remixing of known concepts to solve new problems. Many were fueled by the Age of Enlightenment (circa AD1650-1820). Preparing the way was Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press. He had a dream to make education accessible to all, but how was he to achieve that? He blended his awareness of tried and tested "knowns", adding mechanical power inspired by the wine press, and revolutionizes affordable knowledge acquisition, by inventing a printing press.

Many of the world’s inventions were often a remixing of known concepts to solve new problems. Many were fueled by the Age of Enlightenment (circa AD1650-1820). Preparing the way was Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press. He had a dream to make education accessible to all, but how was he to achieve that? He blended his awareness of tried and tested "knowns", adding mechanical power inspired by the wine press, and revolutionizes affordable knowledge acquisition, by inventing a printing press.

Illustrating printed text was the next challenge: a variety of techniques evolved over the centuries, from wood block stamps, to engraved metal plates to limestone blocks. The drivers for new techniques were human population growth, new materials, and finally demand by an affluent Merchant (Middle) Class creating price efficiencies. Printing houses, employed an army of engravers, lithographers and artists who were called upon to improve recorded detail for scientific classification purposes, botany being an important driver of such skills. Different cultures, with access to their own skill-sets & available materials came up with a variety of techniques to achieve desired outcomes.

Benjamin Franklin & Amateur Naturalist, Joseph Breintnall

If China invented paper in AD105, did they also invent folding money? They did, but abandoned this initiative after a major financial crisis, stopping production in AD1455. It takes a new crisis in the West, for much later generations, to adapt such a concept to need. Yet again, what started out as a blog on the Nature-Printing technique, has lead me down a rabbit hole of discovery.

If China invented paper in AD105, did they also invent folding money? They did, but abandoned this initiative after a major financial crisis, stopping production in AD1455. It takes a new crisis in the West, for much later generations, to adapt such a concept to need. Yet again, what started out as a blog on the Nature-Printing technique, has lead me down a rabbit hole of discovery.

For years I believed the first successful use of Nature Printing was a mid-1800s story. Instead I have scored another “Well, who would have guessed…?” conversation starter dating back to a well-known historical figure over a century earlier. (I am ever-so please as a result, even if the hapless listener is bamboozled by my conversation topic).

The star-spangled hero of this blog is that brilliant polymath, Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). Franklin was just starting his legendary journey of ingenuity. In 1723 this young man had arrived in Philadelphia from Massachusetts with a dream to become a printer, but no fortune did he own. Never one to be idle, he fell in with successful merchant and amateur naturalist Joseph Breintnall. Together they busied themselves inking up New World leaves & pressing them onto paper to send to British naturalists & botanists keen to classify and catalogue New World discoveries. It turns out Breintnall was less a botanist and more in awe of the sheer beauty of his new environment. Franklin, took this knowledge and applied it to a more fiscally motivated project.

Benjamin Franklin's Unexpected Journey of Innovation

Franklin, looking for printing opportunities, became interested in the promising subject of paper money. In essence, what began as hand written promissory notes evolved into dedicated printed "banknotes". In 1690 the Governor of Massachusetts Bay, William Phips (overseer of the Salem Witch Trials), first trialed a paper money experiment to assist funding in the war against France. It must have been a success as the Bank of England adopted the idea in 1694, citing the same reason. Essentially, it was a hand-written IOU issued with a precise amount as a deposit or a loan, to be redeemed after the war. This later evolved into an issuance of fixed denomination printed notes with the various American counties inventing their own currency. Britain was not amused by such a development (enter "frown" emoji), as it assumed a form of independence.

Franklin, looking for printing opportunities, became interested in the promising subject of paper money. In essence, what began as hand written promissory notes evolved into dedicated printed "banknotes". In 1690 the Governor of Massachusetts Bay, William Phips (overseer of the Salem Witch Trials), first trialed a paper money experiment to assist funding in the war against France. It must have been a success as the Bank of England adopted the idea in 1694, citing the same reason. Essentially, it was a hand-written IOU issued with a precise amount as a deposit or a loan, to be redeemed after the war. This later evolved into an issuance of fixed denomination printed notes with the various American counties inventing their own currency. Britain was not amused by such a development (enter "frown" emoji), as it assumed a form of independence.

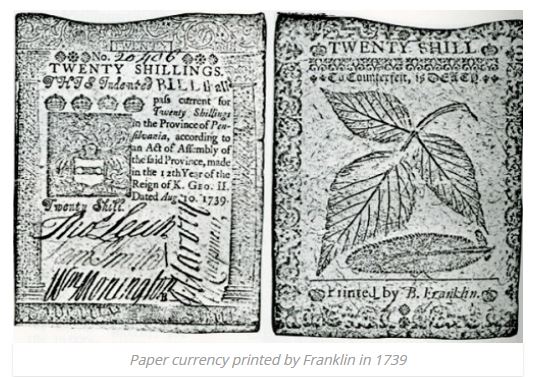

Franklin was a avid admirer of the new paper currency, not least because he was a hopeful printer looking for a paying gig. Indeed, he started printing money for Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware in 1737. However, just like 21st century trolls and scammers learning to exploit new technologies, their predecessors began corrupting the stability of this new form of 18th Century colonial currency. Needless to say, counterfeiters in Britain were one of the many reasons for New World penal settlements across oceans, starting with the American colonies. It seems a natural symbiotic relationship: criminals plus emerging paper currency equals ye olde scammers.

Franklin's Strategies to End the Banknote Counterfeit Conundrum.

Franklin put his innovative genius to the task of thwarting their activities. First, he deliberately misspelled "Pennsylvania" as "Penfilvania" on the official notes assuming a forger would correctly spell it on the corrupted money.The next layer in his cunning plan manifested from his former exposure to the Breintnall's nature-printing project. Exploiting the uniqueness of every one of Mother Nature's leaves, he would add a further layer of integrity to the new paper currency. He adapted the inking up and printing straight from the leaf, aka Nature Printing, to making a plaster impression enabling him to create a lead cast leaf mold to print on the rear of the notes. He further added the insurance of a defining copper engraved lines of the leaf veins. This is known as the first anti-counterfeiting attempt and it owes the topic of this blog to Franklin's 1737-1779 success.

P.S. Another, none-to-subtle message Franklin printed on the 1760s Delaware government shilling note was the slogan "To Counterfeit is DEATH".

Franklin's Nature Printing "Unknown" or just victim of Recycling?

In spite of being a major success in the American counties, it was reported that Franklin’s Nature-Printing technique was "a secret and unknown". In 1914, "three extremely rare 1700s type-metal blocks on deposit with the Library of Congress in Philadelphia (had) been identified as the instruments used to print colonial currency in Delaware". A few generations later, Angela Raymond reports, "His ingenious creation was not discovered until the 1960s when a historian stumbled across the information and shed light to the public". If Franklin listed his technology in a STRICTLY NEED TO KNOWN file it would limit access by any wrong-doers, of course. However, there is also the case that our ancestors were resource-poor, hence excellent recyclers. This tendency was not out of choice, but for pure necessity. Logically, once the soft zinc and copper plates Franklin used had worn down, they were no longer fit for purpose. Why keep them? This precious resource would be melted down, recycled, to recast other leaf molds. This efficient economical reuse model ensured little evidence survived of Benjamin Franklin's ingenious counterfeit solution would have survived its contemporary life. I argue, less "unknown", and more on the "practical recycling" side of the ledger. I am just saying...

© Sandra J I Ker, Antiquarian Print Gallery/History Revisited, Adelaide, South Australia, 2021

.

Recent Posts

- » Lady Sarah Lennox, King George III & The Honourable George Napier

- » Schomburgk's Botanic Garden & Park Plan, 1874

- » "City of Adelaide" Clipper Ship - What is Old Is New Again

- » Napoleon, Hudibrastic Poetry, Doctor Syntax & the Power of Satire

- » Colonial Melbourne to Albury "Parlour Car" Photo Connects to Adelaide Past & Present